As a Youth Group Leader, we’re normally making campfires or baking treats together, so going online wasn’t what we had in mind for 2020. Over a year of online scavenger hunts and mistimed campfire songs put sharply into focus the breadth of skills impacting our group’s online experiences and varied factors affecting how it feels to connect from home. While some of this was borrowing a tablet, getting the video call software up and running or working out the functionality of the mute button; I noticed further dynamics at play. For instance, the environment at home, eavesdropping siblings, or some unease in deciding when to speak up without the usual “in person” cues.

Almost half of young people (48%) are primarily teaching themselves digital skills, equivalent to 6.9 million young people

Since joining Nominet’s Social Impact Team one month ago, I’ve had the privilege to meet some amazing organisations working in the digital skills arena and as I learn more, I see some of the golden threads coming together. Firstly, I’ve heard about the importance of breaking down what we really mean by “digital skills.” One commonly referenced definition comes from the UK Department for Education’s essential digital skills framework and the Digital Youth Index introduces an early question on digital skills which focuses on those foundational skills young people utilise for tasks like accessing an online classroom or communicating via email or chat.

It’s clear there is a need to extend the framing beyond the foundational to consider broader types of digital skills. Some upcoming research with Catch 22 and Livity is looking at conceptualising digital skills for work across all sectors (writing your CV in a job application or using collaboration tools when in work) through to advanced skills for pursuing careers in tech (like data analysis or software engineering). At face value, this spectrum is quite technical, and what sparks my interest is a further, more complex set of relational skills around what it takes to thrive in digital spaces. By this, we might include things like who to trust online or how to keep balance with how much time we spend on social media. In other words: not just digital skills, but skills for a digital age.

You may get a qualification that represents a common standard for the maturity of your functional digital skills – in other words your literacy or capacity. In contrast, when it comes to the more meaningful involvement in a digital life, there can be no single measure nor binary “digital divide” that makes you either in or out. It’s not fair to treat young people as a homogenous group, instead, we need to seek to understand different needs at different points in individuals’ lives and how these may change from day-to-day and even hour-to-hour. For example, I might have a great internet connection in the morning but that same connection buffers when someone in my household is trying to stream a movie. I might feel super confident in my online maths class, but English makes me squirm.

This is where the Digital Youth Index’s emphasis on a young person’s behaviours, attitudes, relationships, and situations (BARS) comes into play and how these complex dynamics manifest at the intersection with digital spaces. For instance, in the Youth Group I support, we had some members drop out not because they didn’t have a device or connection, but because they found the online format too overwhelming or stilted. Some said they felt tired after spending so much screen time during in the day for school which highlighted how feelings and perceptions played a huge role in use of digital technology.

The methodology and resulting insights coming out of the Nominet Digital Youth Index focus on starting with young people; not just zoning into the standalone interface with technology and digital infrastructure. The data behind the Index coupled with the filter and compare features on the platform has the potential to become a powerful new reference point to deep dive into the context and demographics of young people in all their diversity.

One of the most striking findings from the Digital Youth Index for me was how almost half of young people (48%) are primarily teaching themselves digital skills, equivalent to 6.9 million young people, often by its nature informal with little input from parents or teachers. We’ve also uncovered a disconnect between messaging on safety online that lands with parents and carers compared with young people.

This must lead us to ask about the implications for where skills are taught or where they are learnt – and in turn how the appropriateness of different methods varies depending on the type of skills. Teaching is “imparting knowledge to someone as to how to do something” whereas learning is the “acquisition of knowledge or skills through experience, study or being taught”. Some digital skills might be suitable for being taught in an IT lesson in a computer classroom. Others might lend themselves to being embedded in personal, social, health education. Whereas others will never be taught but picked up right across different areas of our lives. For example, using a gaming platform to interact with strangers might change perceptions of trust or deciding to have a ‘digital detox’ might remind us about regaining balance for wellbeing.

So, if skills aren’t just for the curriculum, what different approaches land with young people? How do we create sandboxes for young people to learn and make mistakes, especially when your digital footprint on the internet follows you around forever and the potential harms are very real? What methods are proactive – like building resilience – compared to reactive – like offering support when you’re worried you’ve made a mistake? What minimum standards do we need to ensure everyone is equipped with across a wide interpretation of digital skills? How do tools have to adapt to allow for the ability to make your own contextual decisions and to take control of your own healthy relationship and balance with technology? Is it a rallying call to adapt methods to consider a diversity of options including more peer led, applied or vocational learning spaces? Exposing newcomers to the Internet without building inter-relational resilience skills seems like a learner driver not knowing what a seatbelt is before turning the key in the ignition of the car.

What’s interesting to me, not least in my role as a Youth Leader in a space that’s informal and voluntary, is the dynamic of peers. How are peers there for each other – to share skills, learn from mistakes and discuss experiences. There is a huge range of approaches in the fantastic organisations I’ve met – who focus not just on protecting yourself (like making a super strong password) but acting in the interest of others in a digital space (like a bystander who speaks up when witnessing something that’s not OK). There are fantastic examples of building this spirit in the digital skills community, such as The Scout’s Digital Citizen Badge which sets out to frame skills as citizen first, not digital first and the ChildNet Digital Leaders Programme – a youth leadership training programme empowering young people to educate their peers about online safety. Skill sharing between peers marks a shift from individual to collective thinking which is so desperately needed to plug the gap where digital spaces are not working – where peers play a role in gaps where formal training isn’t landing. Demonstrating in practice how the shift in focus from operational or transactional to the cultural or “hearts and minds” of why things matter can be transformational.

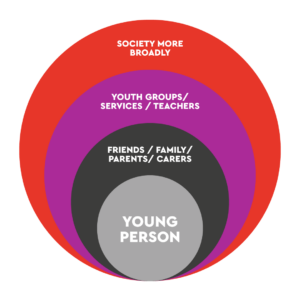

If we are to ensure we leave no-one behind, we must think structurally in multiple, cross-cutting spectrums in the way digital spaces mirror inequalities in society. In many instances, digital realities even exacerbate these inequalities. It’s a much-repeated lesson that digital is not a passive equaliser, so can we pinpoint what new forms of inequity are becoming apparent that can be put down to changes in digital access and skills?

My fundamental motivation to join the Social Impact team is a question of equity – instead of one size fits all, we need to be tailored and intentional to bolster the opportunities of those disadvantaged by society in a way that seeks to level the playing field. Not everyone will benefit from the same type of digital skills training. We need to go deeper to understand the spectrums of disadvantage leaving people behind in multiple, intersecting skills gaps.

The Nominet Digital Youth Index offers us some of this context and nuance: the demographics and experiences directly from young people. It might be a baseline now, but the promise is opening interesting questions as we track longitudinally not only the uptake of formal digital skills, but cross cutting skills for a digital age.