Late 2019 I decided to submit a talk to the Open Source Strategy Forum conference, an annual event hosted by FINOS, an organisation that fosters open source collaboration within the financial services industry. While organisations like FINOS, and its parent company Linux Foundation, have helped big banks and corporates better understand and ‘back’ open source projects, I do feel that their focus is skewed towards the bigger more ommercially-oriented projects.

As a result, the ever-growing collection of small, yet critical, open source projects that are the foundation for so much of what we do continue to lack investment.

As ever, there is an xkcd that neatly illustrates this problem:

My plan for the OSSF conference was to do a deep-dive into a popular open source project to show its complexity, and highlight the associated fragility. Ultimately I wanted to draw an analogy between the problem illustrated in the above comic, with the 2008 financial crisis, where the complex structure of financial instruments hid the underlying exposure to sub-prime mortgages, which ultimately failed and caused a collapse. Surely this would raise a few eye-brows and generate some interesting discussions!

My talk was accepted and I was keen to stimulate a lively debate. However, sadly this conference was pushed back to later in 2020, and became a virtual event. Unfortunately virtual events work reasonably well for passive consumption of content, but are a poor substitute for more active debate and discussion.

As events are likely to remain virtual for much of next year, I thought I’d reproduce my talk here, in the hope that I can create some debate in the online world!

I want to tell you all a bit of a story … I’ve been getting increasingly concerned about the complexity of our open source software.

Software architectures are becoming increasingly componentised, and more often than not, these components that form the foundational building blocks are open source. However, before adopting an open source component, I try to ask myself; Who writes this code? who maintains it? is it a sustainable project? and ultimately, am I going to regret using it? In other words, is the short-term benefit of using this building block going to be eclipsed by some more long-term maintenance issues.

These are not easy questions to answer and more often than not, I don’t see people even attempt to answer them. I’ve seen some surprising choices made in the past, with open source projects that are clearly not maintained or sustainable being selected as a important foundational components for a project.

Complexity and fragility go hand-in-hand. When a foundational component fails, the entire product built on top of it fails. There are also a great many ways a failure can occur, from something quite sudden and critical, such as a security vulnerability, to the more gradual erosion caused by a component that is no longer actively maintained.

To turn this into something concrete, I decided to focus on a real-wold example, by picking a popular open source project and taking a deep-dive into how it is composed.

I opted for ExpressJS, a 10 year old project with 50k stars on GitHub and 15m downloads per week on npm. A project that I have used myself a great many times.

Surely a good choice?

So let’s start asking ourselves the important questions (Who writes this code? who maintains it? is it a sustainable project? etc)

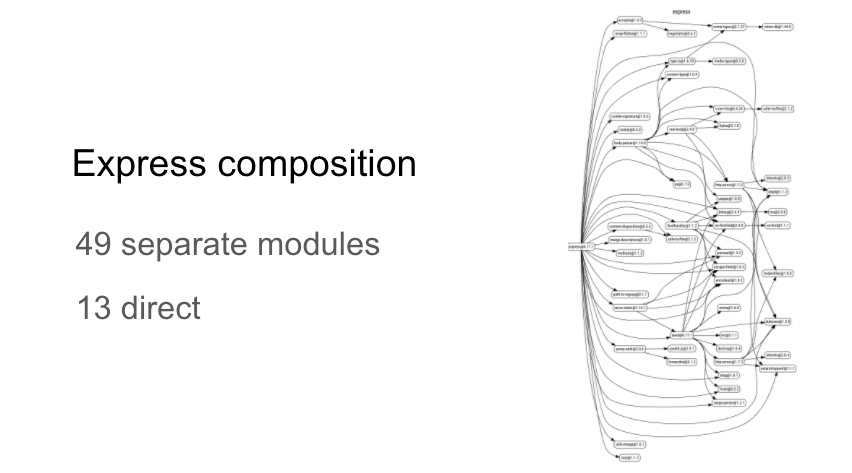

The first thing I want to do is gain a better understanding of the composition of Express. By looking at the dependency graph I can see that it is composed of 49 seperate modules (or packages):

When you install Express on your machine, these dependencies are resolved (and their respective dependencies reursively), and downloaded as part of the installation process. As I observed earlier, modern software is highly componentised.

This is quite typical, not just for JavaScript-based projects. You’ll find similar dependency graphs for projects written in Rust ior Python.

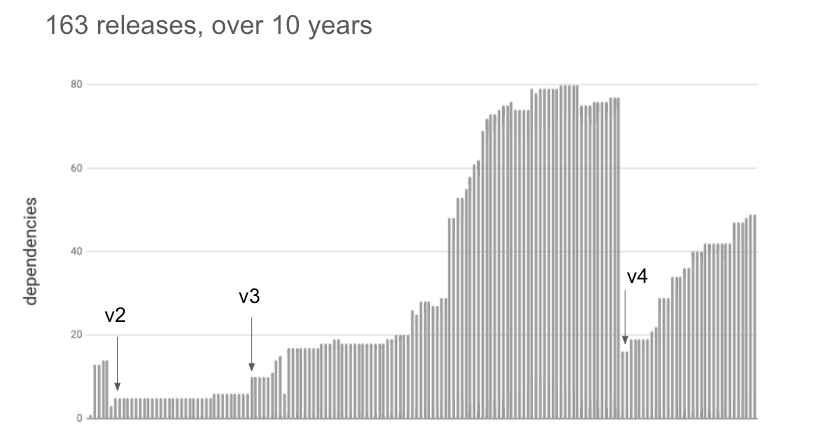

I was interested to see how this had evolved over time, so I downloaded all the 163 releases of Express and plotted their total dependencies:

You can see that Express itself has become increasingly componentised over time. Interestingly, the number of dependencies dropped significantly when v4 was released, only to start rising once again. Major releases are often a convenient time for consolidation and clean-up.

I can see the benefits to a more componentised approach, these high-level building blocks allow you to quickly assemble new and novel solutions (for example a few years ago I wrote my own static site generator in little more than 100 lines of code). However, if I’m trying to assess the overall health of Express, I’m not just checking 1 project, I’m now checking 49 of them!

However, this dependency graph is only half the story. Projects like Express have an additional set of dependencies that are used during the development process. In this case, Express has a total of 195 development dependencies when the dependency graph is fully resolved:

Should I care about or be worried by this? Whilst these dependencies are not shipped as part of the Express distribution, they can have an impact. There are an increasing number of software supply chain attacks being reported, where attackers target vulnerabilities in the development dependencies, or build pipeline in order to insert malicious code.

This is starting to make me a bit nervous, but let’s go a bit further down this rabbit hole. When I install Express what exactly am I installing?

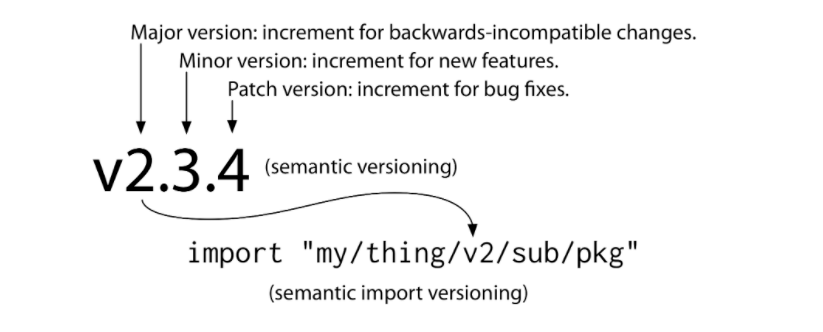

Semantic versioning was proposed 10 years ago by one of the founders of GitHub. It is a simple mechanism that conveys meaningful version numbers as illustrated in the diagram above. Notably 0.x.x versions don’t follow the same rules as 1.x.x versions in that any change can be breaking, in other words, 0.x.x versions aren’t really semantic!

10% of Express dependencies carry 0.x.x version numbers, and as a result you have no way of knowing whether a version increment will carry a breaking change.

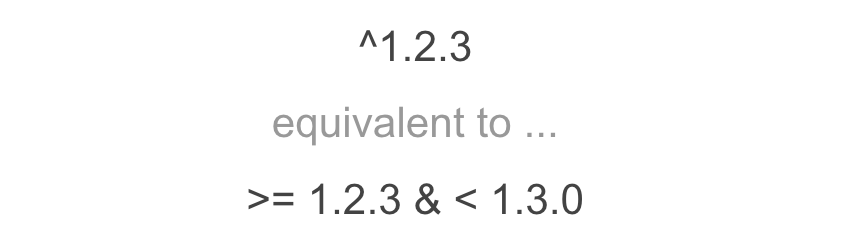

Furthermore, it is common convention to express a dependency on a version range rather than a specific version number. For example, the following range permits bug fixes and new features, but no breaking changes:

I must admit, I’m not sure why you would want to do this! What this means is that for a given dependency, at some point in time in the future, your declared range might result in a new version arriving as part of your installation, with new features and bug fixes. However, without writing additional code yourself, how are you actually going to make use of these new features? and worse still, who determines whether a bug is a bug, or a feature? You could have a workaround for a particular bug, or might even consider it a feature. This new version will cause things to break in either case.

It sounds like a nice idea in theory, but in all honesty, I just can’t see any of this working in practice. I like my software to behave repeatably and consistently. Bugs and all.

Considering that Express has ~200 dependencies, I started to wonder how often one of these would release a new version that was compatible with the dependency version ranges declared by Express, resulting in a different version of that component being downloaded.

The answer is, quite often!

Between just two versions of Express, over a 7 month period, releases in dependencies result in 33 differ configurations.

As an aside, there are various techniques that can be employed to remove this variability. For example you can use a lock file to pin your dependencies to a specific version. However, this is an opt-in process that is not without issues. For starters, yarn and npm have different lock formats (I’ve wasted a lot of time trying to track down an error only to discover I’m using the ‘wrong’ package manager), also they are a bit of a security blindspot.

OK, now I’m getting scared! We have a complex dependency graph, that is ever changing. But where does this code cme from? Who holds the keys? and who decides what is released and lands on my machine?

For JavaScript projects, npm is the package manager and repository that holds the released artefacts. For Express, this is the 49 components / packages that are deployed to your machine on installation.

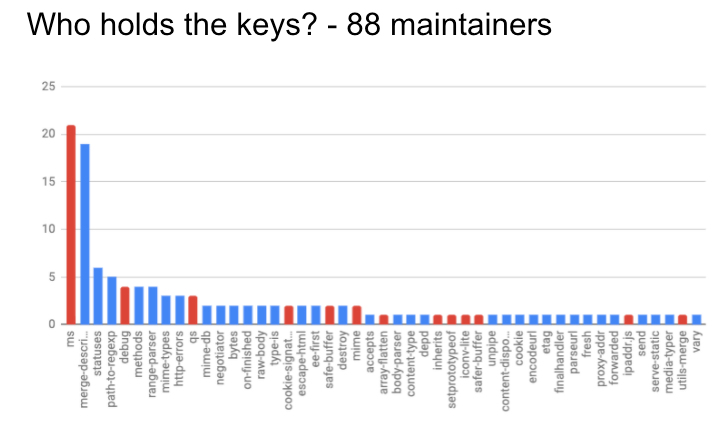

I took a look at npm, and found that these packages were ‘governed’ by a total of 88 maintainers. The following chart shows the number of maintainers for each package:

Those coloured in blue are ones where the maintainer for Express itself is also a maintainer.

Here’s an interesting interesting statistic for you … only 9.27% of npm maintainers have 2 factor authentication enabled. What this means is that if you obtain a maintainers username and password, you are free to publish new versions of their package, releasing malicious code into the wild if you so wish.

From inspecting the package meta-data, I now have the email addresses of these 88 maintainers. I typed the first one into have I been pwned?, and sure enough, passwords associated with that email had been exposed in a number of recent data breaches. Given 88 maintainers, the lack of 2FA and people’s habit of re-using passwords, I think the chances of gaining access to one of the packages that ships with Express is really quite high. No, I didn’t try.

I think we’ve gone far enough down this rabbit hole. A project like Express brings with it a lot of complexity, which in turn can result in hidden fragility.

Here’s a recent example of how a small seemingly innocuous package that is relied upon (most often indirectly) by a great many other projects can cause the whole structure to fall apart:

Let’s take a break from diving into the dependency graph and look at Express from a different perspective – funding.

Who writes this code? who triages the issues? who maintains the project? and how are they rewarded for it?

From looking a the project activity history on GitHub it is pretty easy to determine that with the vast majority of commits coming form a single author, that this is effectively a solo project. I took a look at the website and README and can see no obvious funding model, whether through individual donations or corporate sponsorship.

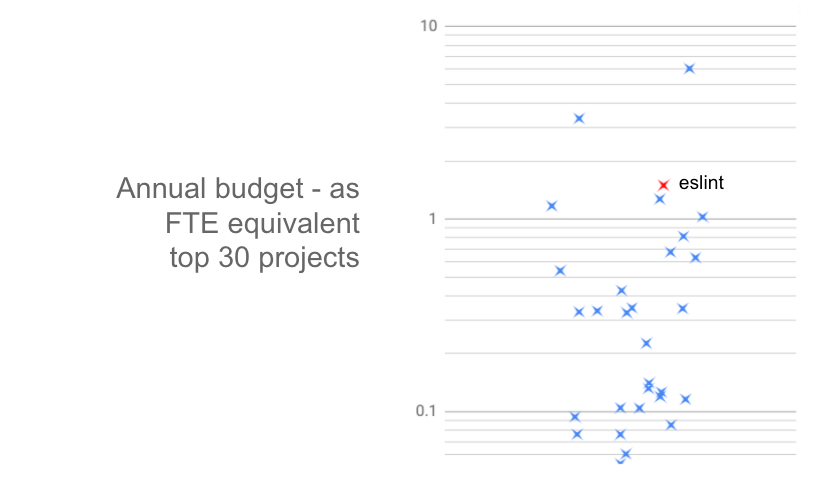

I also looked at the Express dependency graph and of the ~200 packages / projects this includes, I could only find one that was funded, and that is eslint, a linting tool for JavaScript.

Eslint is a member of Open Collective, a company that provides a funding platform for open source projects, handling one-off and recurring payments, whilst also providing lightweight due-diligence on how this money is spent.

Eslint has a variety of company and individual backers:

So just how much revenue does this generate? Eslint is one of the most successful (i.e. funded) projects on the platform. I took a look at the top 30 projects (by funding) and converted their annual revenue into a rough full-time-employee equivalent:

As you can see, Eslint raises enough to theoretically employ 1.5 developers. Most of the top projects raise considerably less than this, and the long-tail of projects that fall outside of this top 30 earn even less still.

For most projects this funding model is an added bonus, and not a means for sustainability of itself.

However, open source maintenance isn’t all about money. A great many maintainers invest their time, love and energy into their projects simply because they enjoy the creation process itself. Unfortunately burn-out is a very real issue in open source, especially for those that do it for the love rather than the money. Once the pressure of maintaining an open source project become too great, and the joy is gone – what reasons are left for continuing?

Sadly while exploring the (lack of) funding for Express I found this tweet:

Without going into the details, a potential security issue with Express was highlighted. What followed was various differences of opinion, quite a lot of “security theatre” (commercial security products labelling Express as insecure), hostility and heated exchanges. As a result, the maintainer publicly stepped away from the project for a short period of time.

I must admit, I wasn’t expecting this. I picked Express quite by random. It is a mature, popular and widely used project. It is funded by Open Collective, it is also a member of OpenJS, a Linux Foundation project for supporting popular JavaScript projects. However, if I was making a cold hard assessment of its long-term viability, I’d have some serious doubts!

The whole ecosystem seems so fragile. I can only conclude that the only reason this all works is that the vast majority of people are good.

… but we sure as heck don’t make it easy for them!

So what has all of this got to do with banks, financial services and large corporates?

I’d say that broadly speaking people are aware that there are risks associated with open source consumption, and that care should be taken when determining which projects to make use of. However, much of the focus is on legal and compliance, (e.g. checking licencing or copyright compatibility) and security. There is very little attention or concern expressed about the maintenance and long-term sustainability of these projects that are being consumed.

I do feel that the overall approach is somewhat medieval – with those within the castle taking the fruits of the labouring peasants that reside outside!

In practical terms there is a lot of time and hard cash spent on security scans, licence checking, internal repositories containing sanitised code and internal forks.

This quote from an open source developer on his encounter with a security software vendor at an open source conference sums it up quite nicely:

So this means that they charge a 50-person startup a whopping $30,000 per year to help them feel safe using code that open source authors like me have given away for free.

These products that make people ‘feel safe’ in their consumption of open source software can also have quite a negative impact on the open source software they are helping you consume. There are many automated tools that helpfully raise issue and pull requests when they feel something within your open source project requires attention, a potential security vulnerability or perhaps a potential version bump.

Unfortunately in practice, this tends to generate nothing but noise and distraction. For example, dependabot bombards me with dependency ‘bumps’ due to potential security issues almost every week.

However, just because a piece of software has a potential vulnerability, that doesn’t mean it will actually manifest itself as such in the product it is being used to create. In practice the vast majority of pull requests I’ve received from this bot are never going to result in a security vulnerability because of the way in which I use them (e.g. they might only be used at build-time, or are not executed client-side, or don’t received un-sanitised input, or …).

Unless this bot gains a better understanding of the context within which a dependency is used, it is always going to generate an excessive amount of noise.

This is an example of security theatre, highly visible activity that gives the impression of improved security, whilst doing little to achieve it.

For open source maintainers this can be quite exhausting. To quote on such developer:

If it’s not fun anymore, you get nothing from maintaining a popular package

So what is the solution? It’s not money, it’s not sanitisation and security scanning. It’s not creating a your own castle to protected your forked projects.

Personally I think the only way to come up with an effective solution is to have some empathy. You need to understand the open source ecosystem, what makes it thrive and what causes it harm. You need to understand the motives of the different participants.

This is a huge topic, and not one that I’m going to dive into in an great detail. What I will do is strongly recommend that you purchase and read the following book:

“Working in Public: The Making and Maintenance of Open Source Software” by Nadia Eghbal – a fantastic book that really dives deep into the open source community to find out how it works.

A few points that have really stuck with me …

GitHub has completely changed the open source community, and this change has been both good and bad. Early open source projects were disparate; little clubs and cliques which formed close-knit communities. People tended to have long-running relationships with these communities. With the rise of GitHub, most project and people now share a common platform. This has made it much easier to contribute to open source projects, however, these contributions are much more fleeting. Nadia compares GitHub to the types of community you find on YouTube, where you have solo creators and a sea of consumers.

For the creators, their most prized asset and scarce resource is attention. Open source developers have limited time to spend on their creations, and they hope that this time spent is fun. A growing number of fleeting interactions and well-meaning contributions (of limited value), security theatre, and numerous other distractions mean that their attention is consumed by tasks which they simply do not enjoy. GitHub has unfortunately made it too easy to contribute.

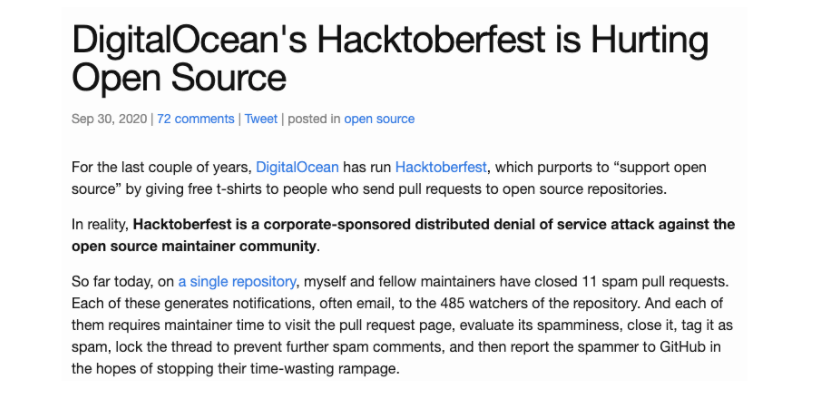

A great example of this negative cycle, limited attention and ease of contribution, is Hacktoberfest. An annual event from Digital Ocean that encourages and incentivises open source contribution by giving away T-Shirts. Sounds good in practice? But this year it fell apart quite rapidly:

Open source maintainers were flooded with exceedingly poor quality contributions, to the point that they branded it a ‘denial of service’ attack.

Digital Ocean certainly had good intentions when they staged this event. However, they misunderstood and misjudged the dynamics of how the open source community works.

So what should Big Bank, or Big Corp be doing to make a positive difference? I’m afraid I don’t have all the answers, but I do have some ideas and recommendations.

As you can see there are a lot of practical things you can do to help create a more sustainable open source ecosystem. However, to make this work you need to allocate time and/or budget, simply relying on the good will of your development team, or out-of-office-hours contributions just doesn’t cut it.

There is much in common between the challenges of open source and the environment that causes the financial crash of 2007. In both cases there was a lack of understanding and an unwitting exposure. What I hope is different is the way that we tackle these challenges!

Join the conversation

I’ll be giving a talk on this topic at the Open Source Leeds meetup event on Weds 29 September. Having described the problem here, I’ll be offering in my talk a starting point for a discussion around a possible solution in the form of the Corporate Social Responsibility model. You can attend in person or via the live stream and there will be plenty of opportunity to ask me questions and share your insights.

You can find out more and book your place on Meetup.com.

Originally posted here