4 steps for local government digital leaders

September 2016

This post follows on from work on Camden’s digital journey, the take-up of digital strategies and the extent devolution to Metro-Mayors and Combined Authorities is ‘smart devolution’. It proposes 5 steps to address the collaboration deficit across local digital public services, critical questions and actions for digital leaders in city halls and Whitehall to help write the missing chapter on ‘Cities and Local Government in UK digital policy.’

Since 2010 the UK has seen strong digital institution-building with GDS, Tech City, the Catapults, the ODI, Nesta and many successful university-based partnerships. Whitehall is now providing a strong national strategic setting for innovation through latest UK Digital Strategy and new Government Transformation Strategy, both launched earlier this year. Yet, the role of Town and City Halls — responsible for 80% of services citizens experience — is absent from such documents and remains to be written. Moreover, devo-deals for cities and Combined Authorities have been struck with limited reference to transformation and the digital strategies remain low in number and of variable quality.

Over the past 18 months discussions with local government leaders and service directors has revealed a rich seam of innovation and ambition in councils across the country, but far too little scaling of what works best. I’ve shared platforms with the IT and Govtech sector who have expressed great frustration that this innovation is often isolated with stubborn barriers to entry persisting across a very fragmented marketplace. I’ve met a new generation of progressive CIOs challenging the old status quo where IT historically has been dominated by a handful of big providers and very many buyers — an ecosystem described by one progressive CIO as ‘sharing without collaboration.’

In each of these conversations there’s agreement that improved digital leadership is critical but we often fail at the second and third question following that — who is best placed to undertake it and what does leadership constitute in practice?

The following is a stab at answering some of these questions.

Today local government experiences a digital transformation ‘collaboration deficit’. Although many councils face the same or similar challenges, their approach to change, the adaptability of their technology estate and how they treat and use data, the fuel for innovation, not only differs but in many cases actually remains undiscovered.

This manifests itself in various ways:

Following the 2017 election there is now a need to correct the balance so that local councils co-ordinate and collaborate and take the lead role in the relationship with the tech sector. Fundamentally successful public service digital transformation will require a more mature regional and national relationship with the emerging GovTech sector to facilitate redesign and reengineering required at every level — workforce, customer service, process, technology, infrastructure and governance — to make our public services faster at doing things, more adaptable and able to share information better.

We don’t start cold. The last few years has seen the creation of new collective vehicles for buying and scaling ‘bleeding edge’ solutions from the tech sector: London Ventures, Bristol’s ‘Programmable City’ initiative, CivTech Scotland, are all exciting initiatives set up by buyers themselves to make it easier for the tech sector to solve public service needs.

i-Network serving Greater Manchester has a strong programme of work aiming to help public services across the north to “collaborate to innovate.” In the capital scoping work for the London Office for Technology & Innovation (‘LOTI’) is starting with discovery missions around existing tech procurement, legacy systems and common standards to assist the new Chief Digital Officer for London in their work. Scotland’s approach has set the pace, with a new CDO and CTO in place and a funded digital office to work with Scottish local councils.

Elsewhere councils are making their own weather. I’ve already written about Camden’s own journey and cited progress elsewhere. Notable earlier this year is the Smart Essex initiative launched in February 2017 by Cllr. Stephen Canning pledges £7m from the 3% adult social care precept for digital services across the county. On a strategic level, work by Tech UK and LB Harrow’s Cllr. Niraj Dattani a new vision of the ‘Council of the Future: Preparing for Smarter Communities’ sees Harrow Council as a demonstrator authority which “attracts, catalyses, and incubates innovation, and the value of doing so.” As part of the programme, they aim to:

“de-risk the concept of innovation; demonstrate the relevance of technology to local authority service delivery; seek innovations which respond to our challenges, rather than the other way around; raise awareness around potential of innovation that could be applied across services; prove theory of technology being able to play a role in addressing our biggest challenges; keep councillors and officers aligned throughout the process; work with the tech sector to demystify engaging with local authorities; demonstrate scale and potential of local government as a market; and finally to provide forum and pathway to implement technology innovations in Harrow Council.”

If these and similar critical questions necessary to probe the potential for wide-scale reform, the issue is whether there should be more strategic support: the GLA’s Natalie Taylor writes:

“Local government has no GDS equivalent, no centralised service standard which must be applied in order for digital services to go live, no centralised spend controls, no Francis Maude at the helm championing the efficiency savings which are achievable through digital transformation.

Local government is different to central government. It delivers more transactional and complex services at a local level, so it probably needs something different to a GDS, but what? And who is thinking about this? Who are the leaders setting the strategy for local government digital transformation across the piece? Yes there are some Chief Executives, Chief Digital Officers and Chief Technology Officers doing great work, but it’s piecemeal.”

So can we contemplate a more direct alignment GDS, Whitehall departments and progressive local government thinking to span public service delivery and scale transformation?

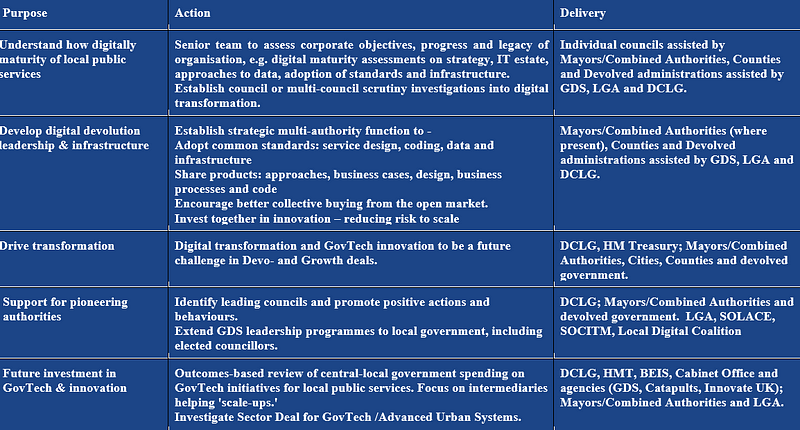

Below I’ve sketched a new framework, developed from my Start of the Possible work, which respects local autonomy but establishes a role for central government to be a strategic digital leader supporting and enhancing the quality and scale of technology adoption.

Step 1: Understanding digital maturity of local authority

Transformation can only progress in earnest if senior political and council leadership can confidently establish the digital foundations of the organisation. For politicians I suggest the three crucial questions to ask are:

(1) How many lines-of-business does the organisation have and what IT is supporting them and how?

(2) How does the organisation hold data from these lines-of-business and other sources corporately and to what extent is it computable and shareable?

(3) How does the organisation buy technology, how open to smaller tech firms is the council and what is the typical sales cycle for Big and small tech providers?

To assist health and social care integration councils and NHS trusts are undertaking NHS digital maturity assessments to provide a better picture on digital and information sharing, whilst highlighting opportunities. In the future discovery should be broadened to identify current and future infrastructure needs; cyber-security essentials; approach to open data; place-based needs (e.g. embedded technologies in the public realm or with services) and digital skills of the workforce. The current scoping work for the LOTI, explains the GLA’s Andrew Collinge, is “an assessment of the boroughs’ digital assets and capabilities and what can add value and provide efficiencies, and a focus on open standards. Where we want to get to is to have some clear workstreams that groupings of local authorities think they can sign up to, and for that to be underpinned by an operating model that sets the business case.”

An important strategic first step for government and the LGA would be to consider the use and development of maturity assessments and how they can be adapted by local councils right across the country. Broadening the discussion away from senior teams is important to capture concerns about digital exclusion, skills and the economy which might impede change— LB Ealing’s Digital Services scrutiny is an example of this which could be replicated elsewhere.

Suggested actions for councils:

Step 2: Digital devolution leadership and infrastructure

Directly-elected Mayoral elections in new combined authorities in May 2017 are almost certain to give further expression to the digital transformation agenda as the competing candidates position themselves as champions of the new economy and more effective regional public services. Combined Authorities, and regional/sub-regional collaboration — present opportunities for councils to buy at scale, spreading risk and enabling solutions not normally open to individual councils.

The concept of subsidiarity — where challenges should be resolved at the most local level relevant to their resolution- is supercharged by devolution: some areas of policy are best dealt with by the Town or City Hall (licensing, planning, estate regeneration etc.) but others such as apprenticeships and skills, transport planning public health or social care integration or big infrastructure require joint-working across borders entirely with councils and other public services sharing data and products.

Tech UK have conducted important work setting out priorities for new Metro-Mayors, including new innovation teams and a Chief Digital Officer. Developments in this areas are likely to be supported across local authorities councillors recently surveyed strongly agree “councils should procure more technology functions together” and supported the proposition that devolution include Chief Digital Officers to drive digital transformation across authorities.

Suggested actions for Town- and City- Halls:

Step 3: Driving transformation

The third feature of the new framework makes digital transformation a much more central part of devo-settlements. As I argued in my analysis of existing devolution settlements, ‘digital transformation’ as a term is not specifically mentioned in any of the deals. The deals fall short on expressing progress around common standards, digital governance arrangements, smart city ambitions, infrastructure or anything more than a general assurance around integration.

The absence of digital transformation in devo-deals is often put down by government officials as not wanting to impose undue burdens on local government or impose a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. Yet local authorities have signed off ‘Efficiency Plans’ in return for 4 year funding settlements with CLG and HM Treasury where they were asked to set out their transformation goals, but not necessarily how they would do so through the use of technology. If this mechanism exists, who not use it to seed at least some critical questions.

Directly-elected Mayors for Combined Authorities are being encouraged by the tech sector to accelerate digital transformation in practical terms through Chief Digital Officers and innovation teams leading to more effective system interoperability and developing greater shared technical expertise, data sharing and joint procurement.

Suggested actions for Whitehall:

Step 4: Support for pioneering authorities — a ‘coalition of the willing’ in local government

It is not considered desirable to expect all local partners to implement the same systems, nor realistic for all authorities to commit to the same pace of change. The current landscape ranges from leading outliers who see digital transformation as a core part of their journey through to those under contract with big suppliers and those who do not see this as a priority.

What speed should reform in local government take? Should we support a narrower ‘coalition of the willing’ in the country already establishing themselves as leaders in this field in data, AI, embedded technologies or digital services? Such a network, defined by capability and political/corporate commitment and supported by central resource, could be demonstrate the ‘art of the possible’ to other councils and provide valuable learning on transformation as well as clearer routes-to-market for GovTech services seeking proof or scale.

Suggested actions for all:

Step 5: Future investment in GovTech

Leading councils are using data to budget more effectively around outcomes and adopting common standards around designing services around user-needs. Investment in datasets such as open data and business intelligence tools are giving councils a repeatable and systematic approach using public and private data sources for the discovery, preparation, analysis and delivery of insights. We are starting to see how Artificial Intelligence and machine learning in medical research is leading to the prospect of clinical and operational improvement in the NHS. Intelligent or robotic process automation for high scale transactional services such as human resources, finance and customer services will be another area for councils to explore with the aid of curated or even cross-over solutions from GovTech firms.

The private sector is already active in this market and loos likely to grow. EY acts as integrator to the London Ventures programme for London Councils. New growth programmes for GovTech have been established: research undertaken by one of them, Public, estimates that the UK GovTech market could be worth £20bn by 2025.

The question for central policy makers, following the progress of the steps set out above, is whether this money is invested effectively, or whether there will be new opportunities to collaborate ever more successfully with local government, for example through a Smart City or the Advanced Urban Systems Sector Deal proposed in March by Future Cities Catapult. Consideration to market-stimulating initiatives such as Ripple Foundation’s 1% Campaign on open source spending.

Possible actions for Whitehall:

Conclusion

The break of the 2017 poll, the election of Metro-Mayors and their combined authorities brings into relief the need to address this policy gap in a more strategic way. City and regional devolution really needs to be smart devolution. Using digital technology to redesign and rebuild services to be simpler, clearer and faster for people to use is increasingly critical to effective public service delivery: developing services designed around user need; saving money by increasing automation and reducing duplication; and allowing government and the public to see how effective interventions are and what level of government is most appropriate to solve problems.

In 2016 DCMS published research on the current and future supply and demand for digital skills in the UK economy: a similar exercise should be undertaken around digital local public services. In the context of Brexit/Industrial Strategy, the longer central and local government remains uncoordinated around digital, the less innovation will be captured and greater the risk that the markets will look less positively on the UK’s broader virtues as an economic power, a tech hub and magnet for foreign direct investment.

If these objectives are to be delivered, then newly -elected city and regional mayors will need new tools, teams and thinking to match their new powers. Together with government — aided by a joint discovery exercise — it is surely time to write that missing chapter.

This was originally posted here, and was reposted with permission.